'I can tough it. I made it this far.'

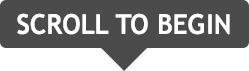

Special to the Democrat-Gazette/TEXSAR

A searchers fanned out across the desert in Big Bend Ranch State Park as they looked for Cathy.

IG BEND RANCH STATE PARK, Texas — By 6 a.m. Sunday, the number of searchers had grown to 40.

Tents dotted the bunkhouse area. Dog teams were en route from Austin. Dozens of green Ford pickups with the Texas game warden logo had overtaken the parking area.

Searchers felt confident they would find me. But most feared this would be a body recovery, not a rescue.

I had been lost in the desert for four days and four nights — two of them alone — with too little water.

The county sheriff put the justice of the peace and a funeral home on standby. Other volunteers saddled up horses that wouldn't spook if they had to haul out a dead body.

A few people still hoped that I would be found alive. Just in case, an air ambulance waited on a landing strip at the state park.

Searchers divided into six teams that would cover an area encompassing three steep ridges. Each team had a medic, a radio and a satellite phone.

"Remember, we can't expect her to be conscious, awake or able to hear us," game warden Brent Tucker reminded the group.

Even Tucker had planned for the worst. Before setting out, he tucked a body bag into his backpack.

No one wanted Rick to see my remains. So when the teams left, assistant park superintendent David Dotter kept Rick at the trailhead.

"How long can you live without water?" Rick asked.

Dotter didn't answer. But a nearby volunteer had overheard.

"Three days."

Dotter cringed, but Rick took the answer in stride.

Meanwhile, the volunteer peered through a pair of binoculars.

"Hey, what's that guy doing?" he asked.

It was Fernie Rincon, who appeared to be wandering randomly along a ridge.

Rincon is a state park police officer at Franklin Mountains State Park in the northern Chihuahuan Desert. He is intimately acquainted with the desert's deadly capabilities and well-known throughout West Texas for his skill in finding lost hikers.

"I don't know what he's doing," Dotter said. "But if anybody knows how to search, it's him. Whatever he's doing, it's the right thing."

David Dotter

Fernie Rincon

s the six teams wended their way through the desert, volunteer searchers Shawn Hohnstreiter and Andy Anthony repeatedly called out for me.

Once, Hohnstreiter thought he heard a response.

He yelled again.

Nothing.

At 11:30 a.m., the team stopped briefly for lunch, then resumed walking.

Meanwhile, Rincon and game warden Isaac Ruiz had separated from the rest of their team to scramble down into a deep valley at the foot of the last ridge. When they reached their team's rendezvous point at the bottom, the two men decided to take a break.

In the distance, they could hear Hohnstreiter and the searchers on his team shouting in unison from a ridge: "Cathy, can you hear us?"

A woman's voice answered.

"Help!"

Rincon turned to Ruiz. "Did you hear that?"

Ruiz, wide-eyed, nodded.

"Cathy, can you hear us?!" the team on the ridge yelled again.

Those shouts snapped me back to reality. For the first time in 24 hours, I knew where I was and that people were looking for me.

"Help!" I yelled again. "Help me!"

This prompted a lot of hollering from the many searchers within earshot. From where he stood a quarter-mile away, Anthony could see Rincon and Ruiz jumping to their feet.

"Shut up! Shut up!" someone yelled, trying to silence the others so that I could be heard. The commotion prompted Tucker to radio another team to find out what was going on.

"We hear her voice," a searcher told him. "We're trying to find her."

Following my cries, Rincon and Ruiz ran 100 yards or so and peered down into the ravine where I lay.

When I saw them, I yelled again.

Special to the Democrat-Gazette / KEVIN FRAZIER

Texas game warden Brent Tucker helps Cathy hold up her head so she can sip water from a bottle cap.

"Help!"

Somehow, Rincon spotted my bare legs sticking out from under the mesquite tree 50 yards below. Disbelieving, he and Ruiz clambered down into the ravine.

"We've got her! We've got her!" Rincon hollered. "We found her! She's alive! She's alive!

I was naked, feral-looking and babbling about how Rick and I had gotten married at Big Bend National Park 13 years earlier.

Rincon and Ruiz immediately pulled off their uniform shirts and covered my needle-pierced torso. Even then, I continued to shiver violently. My tongue was thick, my lips swollen, and I made little sense to them at first. Slowly, as I calmed down, I became more coherent.

"Thank God, you found me," I said hoarsely.

"Do you know your name?" Rincon asked.

"Cathy."

"Do you know your husband and kids' names?"

"Rick, Amanda and Ethan. Is my husband OK?"

"He's fine," Rincon said. "He's why we're here. Do you know what day it is?"

"Friday."

"Actually, it's Sunday."

Special to the Democrat-Gazette / KEVIN FRAZIER

A Texas game warden and Texas Search & Rescue volunteer take a break during the search for Cathy Frye.

ther searchers surged down into the ravine. For days, I'd been alone. Now I was surrounded by a growing crowd. I hadn't been forgotten. All of these people had been looking for me.

I wanted to cry. I tried to cry, but my body was too dehydrated to produce tears. I had so many questions. Where was Rick? Was he really OK?

My rescuers were stunned. I was not only alive, but conscious and talking nonstop.

I asked those gathered around me to tell me where they were from. I told them how much I had wanted to get back to my kids. And

I insisted repeatedly that a mountain lion had watched over me during my time alone.

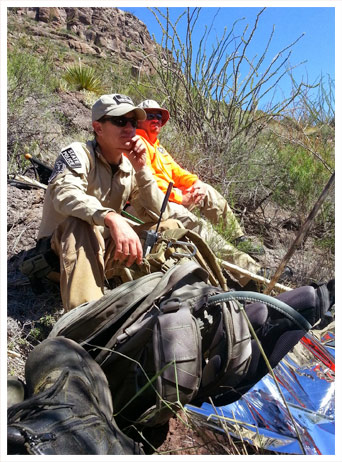

Rincon asked game warden Hallie Rodriguez, the only woman present, to look me over. She asked about my children. I told her I had just talked to them the night before and that they were fine.

I mentioned that my wedding ring had fallen off, and several people immediately began sifting the dirt around my tree. My ring didn't surface.

Tucker and game warden Kevin Frazier arrived, breathless from their sprint to the ravine. Tucker knelt and took my pulse.

"Hey, Cathy, I'm a medic," he said. "We've been looking for you."

"I'm so glad you found me," I replied. "Do you have any water?"

Hallie Rodriguez

ick knew something was up.

After the search teams headed out that morning, Dotter had persuaded Rick to return to the bunkhouse with him. But Rick grew antsy. He wanted to go back to the trailhead.

"Hang on, we'll go," Dotter assured him. "They're going to have lunch. Why don't we wait and eat at noon, and then I'll take you?"

That's when the kitchen phone rang.

A volunteer ran for the kitchen and answered.

"Hello?"

It was Rodriguez, calling from the ridge.

"We found her."

And then static.

The bunkhouse fell silent for a long moment. Then the frantic whispering began. A screen door slammed and Capt. Ray Spears, the incident commander, ran inside, gesturing for Dotter to get Rick out.

Dotter led Rick to the front porch and tried to make small talk. But the ranger's eyes were fixed on the action inside.

Rick knew.

They found her.

He struggled to keep his composure.

Is she alive? Is she dead?

When he heard someone ask, "Where's Rick?" he rushed inside.

Spears greeted him at the door. "She's alive," he said.

Rick collapsed to his knees.

Ray Spears

remained focused on the glistening bottle of water in Tucker's hands.

He took off the cap and poured a tiny amount into it. "Your body's in shock," he explained. "You can't guzzle it. Your organs may have shut down already."

He had to hold up my head so I could drink.

Tucker noticed that if he kept me talking, my shivering would temporarily cease. So he and Frazier bantered with me. Tucker took out his phone and showed me a picture. "We went to your spring," he said, referring to the clearing where Rick and I had spent Thursday night.

"Oh, where did you get the pictures?" I asked.

"Rick," Tucker said.

Frazier chimed in: "We've got some of you dancing on top of a bar."

"That would have been 10 or 15 years ago," I replied.

"Did you hear the coyotes?" Tucker asked. Earlier, he and the other game wardens had found a pack of five or six coyotes assembling 200 yards downwind of me and feared the worst.

"No, but it's OK," I assured him. "The mountain lion was protecting me."

Oookaaay. ... Tucker thought. Time for some more water.

Tucker told me that they were trying to find a helicopter to airlift me to a landing strip, where a plane waited. The Texas Department of Public Safety helicopters weren't available — one was on a call; the other down for maintenance. I could sense that my rescuers were getting antsy. They knew, even if I didn't, that my medical condition remained precarious.

Finally, despite the federal government's shutdown, a Border Patrol pilot volunteered to pick me up in an agency helicopter. In preparation for his arrival, searchers hurriedly cleared a landing zone.

When the helicopter got close, the group loaded me into a cloth stretcher as I moaned, wailed and apologized. Tucker warned that the 15-minute hike to the helicopter would be painful. I didn't care. I wanted out of that desert, no matter how much agony was involved.

"Just do what you've gotta do," I said. "I can tough it. I made it this far."

My first-ever helicopter ride lasted only a few minutes. We landed, and a flight crew loaded me into the air ambulance. I could hear Rick's voice. I have only a wispy memory of his face and grin.

Rick had expected me to be unconscious. But when he approached the helicopter, he heard me giggle.

She's going to be OK.

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette/RICK McFARLAND

Cathy used a small mesquite tree for cover from the sun for three days and two nights after Rick left for help in Big Bend Ranch State Park.

hen I arrived at University Medical Center of El Paso, doctors told me I was only a few hours from death when the searchers found me.

I spent six hours in the emergency room before I was admitted to the Telemetry Unit, located next to cardiac intensive care. There, I would remain under continuous electronic monitoring.

I was in acute renal failure. My heart, lungs and liver were damaged by severe dehydration, extreme exertion, heat and cold. I was diagnosed with rhabdomyolisis, a condition in which muscle fibers disintegrate and enter the bloodstream, often causing kidney damage. My temperature fluctuated wildly, triggering an alarm each time it shot too high or too low. Every four hours, nurses woke me for breathing treatments.

That first night, a nursing supervisor gasped when she saw me. Cactus spines protruded from my back, chest, legs and feet.

Tiny, hairlike needles from the cactus pulp I had eaten remained embedded in my mouth and lips.A young male nurse took hold of some of the longest spines and pulled. My screams echoed through the hospital wing, into the waiting room.

Rick arrived at the hospital soon after. I felt a wave of relief.

He's really OK.

We talked first about the children and my parents. And then Rick told me about the search and how it unfolded.

When he prepared to leave for the night, a nurse asked if he wanted to take any of my valuables with him.

"Well, the only thing I can think of is her wedding ring," Rick said, then noticed my stricken expression.

"It fell off my finger, and I couldn't find it," I told him.

A look of sadness flitted across Rick's face. He'd picked out my ring in 2001 with the help of my closest friend. The first time I saw it was when he slipped it on my finger on our wedding day at Big Bend National Park.

Before he left, we clasped hands, just as we had in the desert when I told him to leave me.

The desert had taken my ring. But it hadn't claimed us.

I called the kids for the first time the next day. The sound of their voices renewed me.

I couldn't wait to see them and hold them. I wanted to kiss the freckles on Amanda's cheeks and nuzzle the cowlick on Ethan's forehead.

Special to the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette

Texas game wardens and Texas Search & Rescue volunteers carry Cathy Frye to the approaching Border Patrol helicopter, which airlifted Cathy out of the desert.

Special to the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette / CLAUDIA LAUER

Rick and Cathy reunited at University Medical Center of El Paso

n Wednesday, Oct. 9, I left the hospital after a three-day stay. My mouth remained full of cactus needles, as did the rest of my body. The medical staff assured me that the needles would eventually surface as my body rejected them.

Rick and I headed to a nearby drugstore to fill my prescriptions. There, in the waiting area, I broke down. No longer sedated, I could finally feel emotion again, and the enormity of what had happened hit me fast and hard.

Back in Arkansas, my parents were watching our children. They hadn't told Amanda and Ethan about my ordeal until after I was found.

But a few hours after letting them know, Mom found Amanda, 10, sobbing inside her bedroom closet with her stuffed animals and our orange tabby cat, Mr. Kitty.

"My mom could have died, couldn't she?" Amanda asked.

"Yes, honey, she could have."

"But she didn't," Ethan, 8, chimed in. "They found her."

On the evening of Oct. 10, nearly two weeks after we'd set off on what was supposed to be a relaxing vacation, Rick and I pulled into the driveway of our North Little Rock home.

Amanda and Ethan waited for us in the front yard. On her wrist, Amanda wore a leather bracelet that I had given her a few years earlier. It came from Big Bend.

They watched as I crawled painfully out of the truck.

I limped across the yard to my children — the little girl with a smattering of freckles across her cheeks and the little boy with an unruly cowlick.

I pulled them close, inhaling their familiar scents, and thanked God for giving me more time to be their mother.

Amanda, now-11, Ethan, now-9