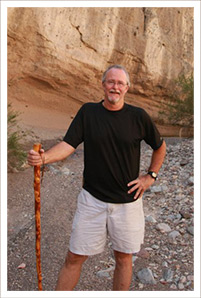

Cathy Frye and her husband, Rick McFarland, wander off a trail in southwest Texas. Out of food and water, the exhausted pair press on in search of help.

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette/RICK McFARLAND

Rick took this photo looking down into Fresno Canyon over the Crawford-Smith Ranch ruins. This was about an hour and a half before sunset on the first day of the couple's hike in Big Bend Ranch State Park.

chilling wind swept across the Chihuahuan Desert, as I repeatedly clenched my jaw to keep my teeth from chattering.

Rick and I lay pressed together for warmth on dirt and rocks. It had been 14 hours since we drank the last of our water. I might have dozed off once or twice. Mostly, I’d been wide-eyed and worried.

Dawn broke between 7:30 and 8 a.m. Rick and I stood up, stretching legs and shoulders that had stiffened overnight. Then we hobbled back down to the last rock cairn we’d seen the night before.

“So that’s what happened,” Rick said, studying two other cairns that led away from the overlook. “We followed the markers to the overlook instead of staying on the trail.”

According to the map, we still had about 6 miles to go to get back to our pickup, which was parked about a mile from the Puerta Chilicote trailhead.

Special to the Democrat-Gazette

Rick McFarland

e hiked steadily for a while, and I began to feel a little more upbeat — until we started losing the cairns again.

Just like the day before, we stopped often to pore over our map. We backtracked and crisscrossed countless times in search of overgrown cairns. This stop-and-go process proved physically and mentally exhausting. Each time we lost the trail, we felt a new surge of panic. Each time we found a cairn, we felt relief and hope.

Ahead of us, the desert seemed to stretch into infinity. The terrain appeared flat. But by now, we knew better. This portion of the desert undulated mercilessly. Dozens of arroyos forced us to clamber up steep hills. After each climb, we skidded down, only to face yet another ascent.

Rick and I became irrationally angry. We cursed the desert for torturing us with this seemingly endless series of arroyos.

Special to the Democrat-Gazette

Cathy Frye

hen will this stop?” I shouted.

“Never,” Rick muttered, plowing through yet another maze of catclaw.

Each time the plant’s sharp, curved “claws” sank into our legs, we had to unhook ourselves before we could continue on. Dried blood and pollen from the tall, yellow flowers streaked our legs.

Each time we stopped to rest, bees swarmed our thighs. We were too tired to wave them away.

The temperature climbed as the sun rose higher.

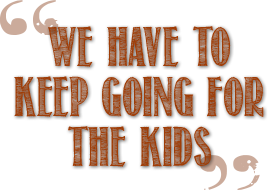

“We’ve got to get back to the kids,” we told each other, our voices hoarse from lack of water.

Amanda, 10, and Ethan, 8, were at home in North Little Rock with my parents, who baby-sit the children each year when Rick and I take our anniversary trip to the Big Bend region of Texas. I pictured their sweet faces, imagining how scared they would be if they knew of our increasingly dire situation.

At 9:53 a.m., we turned on Rick’s phone. Even though we knew the chances of getting a signal were slim, we had to try.

“No bars,” I said.

We sent a text to my dad’s phone anyway:

Call rangers, Rick wrote, including his best guess at our location.

After 30 seconds or so came the expected response from the phone: Not delivered.

Amanda, now-11, and Ethan, now-9

e hiked for another four hours. At 2 p.m., I insisted that we find shade.

I’d read a book called Death in Big Bend by Laurence Parent in which a woman survived the desert heat because she took shade in the afternoon and walked out at night. We wouldn’t have enough of a moon for night hiking, but we could at least keep ourselves from dropping dead during the hottest part of the day.

I saw a large rock formation and veered toward it. One side offered a patch of shade big enough for both of us. Cooler air flowed through a large hole at the bottom of the rock. I sat down next to the hole, reveling in the funneled breeze.

“Wait, wait, let me check for snakes,” Rick said, poking his hiking stick into the hole.

“I don’t care about snakes,” I mumbled. “This feels so good.”

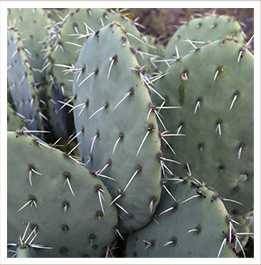

A moment later, a bright green prickly pear cactus caught my eye.

They put cactus juice in margaritas. Surely there’s something to drink in there.

I asked Rick to cut some pads from the cactus. After wresting away two pads, he tried painstakingly to scrape off the spines. Impatient, I grabbed the knife, cut the bottom off one of the pads and sucked some liquid out of it. Then I pulled it apart and started eating the pulp, but even that had tiny, hairlike needles that embedded in my tongue, cheeks and lips. I didn’t care. Even a mouthful of needles couldn’t compete with my thirst.

“This is disgusting,” Rick said, spitting out the pulp. “It’s slimy. I can’t swallow it.”

“Don’t spit,” I told him. “We need all of the water that’s still in us.”

Rick lost interest in the cactus. So I ate his, too.

As we sat there, the deep silence of the desert began to play tricks on us. Our minds began to fill the quiet with imaginary voices and music.

Rick thought he heard a plane.

There was no plane.

But just in case, we put our shiny aluminum water containers on top of our hiking sticks and then propped up the sticks against the rock.

“Help!” Rick shouted.

“Help!” I yelled. But a solitary word couldn’t convey my desperation. “We don’t have any water! We spent the night at the Mexicano Falls overlook! We’re trying to hike to the Puerta Chilicote trailhead! We have to get back! We have two kids!”

“Cathy, nobody’s answering my call,” Rick said. “No one is going to answer yours either. Just save your breath until someone answers.”

So I prayed aloud. “God, please help us. We got ourselves into this situation by being arrogant. We know we were foolish. Please, for the kids’ sake, help us. …”

My voice cracked.

Special to Arkansas Democrat-Gazette / RICK MCFARLAND

Rick McFarland and Cathy Frye cut open the pads of prickly pear cactus to suck out the juice inside. The cactus pulp contained hairlike needles that quickly embedded in Frye's mouth and lips.

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette/RICK McFARLAND

Rick took this photo at the rim on the first morning of the couple's hike. The rim looks across Fresno Canyon in Big Ben Ranch State Park.

on’t cry,” Rick said.

“You can’t spare the tears.”

We lay down and contorted ourselves to fit into the rock’s shade. I discovered a second hole in the rock and pressed my face against it, savoring the musty, cool puffs of air.

Then, with my face hidden, I finally let myself feel all of the emotions — terror, sadness, hopelessness — that I’d been trying to hide from Rick. I thought of Amanda’s adorable freckles, the smell of Ethan’s hair.

God, we have to make it. What about our children? I’d give anything to be snuggled up on the couch with both of them right now, watching a movie.

Tears slid down my face, surprising me.

If my body can still produce tears, maybe I’m not as dehydrated as I thought.

I touched my cheek, and licked the salty moisture off my finger.

As we lay there in silence, our shady patch began to shrink. Rick rolled onto his side and we flattened ourselves against the rock. But soon there wasn’t enough shade for two.

Rick staggered off, out of my sight.

“Where are you?” I called.

“Under a creosote bush,” Rick yelled back.

By now, the gravity of our situation had erased the morning’s optimism.

We have to find water. Soon.

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette/RICK McFARLAND

Rock cairns mark the trails at Big Bend Ranch State Park. Rick and Cathy spent hours searching for cairns in an effort to stay on the trail. Dense desert vegetation had overgrown many of the cairns, making them difficult to find.

hen my tiny area of shade shrank to nothing, I moved to the other side of the rock. After taking off my shoes and socks, I sat on a small boulder and shoved my bare feet into the formation’s largest hole. I put my arms on a ledge and pressed my torso against the coolness of the stone. Then I buried my head in my arms, like I’d once done in grade school.

I felt terrible. Nauseated. Weak. Every so often, I pinched my forearm. The skin I grabbed between my thumb and forefinger stayed folded, a sign of severe dehydration.

Thirst consumed my every thought. I imagined the sensation of liquid in my mouth, coursing down my parched throat. I fantasized about orange juice and lemonade. My lips were cracked and swollen, and my tongue felt thick and useless. Every so often, I swiped a finger around my mouth to scrape out the grit.

When the rock formation’s shade finally expanded, Rick returned. He lay on the ledge just below mine. He didn’t look good. Nor did he want to talk.

“Babe, I’m really worried that we’re not going to make it,” I said, hoping he would contradict me.

“Me, too,” Rick mumbled.

“We have to keep going for the kids,” I said. “We have to.”

Rick agreed but lapsed again into silence.

“When the sun goes down, let’s get a bunch of cactus pads and pound them with rocks to get the juice out,” I proposed. “Then we won’t have to eat the pulp.”

Rick raised his head and looked at me. “Seriously?” he asked. “We have nothing to put it in.”

“We’ll use our water containers,” I explained.

Rick still looked doubtful.

ine. When the sun is less intense, I’ll show him.

This plan occupied my thoughts for a few hours. Then I became convinced that God was going to make it rain. All we had to do was wait. I spent the rest of the afternoon and early evening watching clouds.

Finally, when the sun began its slow descent, Rick perked up.

“We need to get going,” he said.

“Wait,” I replied. “First, we need to eat more cactus. We’ve got to have some fluid.”

And God still has to make it rain.

Rick gathered more pads, and we tried to force down the pulp.

“It’s just gum,” he protested, throwing down his pad in disgust.

I polished off a few more.

“You have to get the really ripe ones,” I said. “They have more juice.”

I also sampled a sprig of mesquite — nasty — and a flower. I put a stone in my mouth, hoping it would activate my taste buds and produce saliva. It didn’t.

ick gathered our belongings. He handed me my boots. Reluctantly, I pulled on needle-studded socks and laced up my hiking shoes.

Those clouds look promising. Nice and gray.

“We’ve got to get going,” Rick urged from a distance, already walking out of my sight.

I stalled for time, but then began to follow him. He hadn’t gone far.

I found him sprawled in a dry creek bed.

“See those clouds?” I asked as I lowered myself next to him. “God told me he’s going to make it rain. All we have to do is stay here with our water bottles open.”

I lay down and balanced my open water bottle on my chest. I made Rick do the same.

Vultures circled overhead. I flipped them off.

y bizarre behavior began to unnerve Rick. “Are you ready?” he asked again.

“We have to wait for the rain,” I insisted, refusing to budge.

Rick humored me for another 20 minutes. I used that time to find God’s face in two sets of clouds.

So beautiful.

“Baby, we have got to get moving,” Rick said. Then, in a burst of inspiration, he added: “Maybe God wants us to follow the clouds.”

That brought me to my feet.

Of course! We must follow the clouds!

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette/RICK McFARLAND

Rick found a tiny spring in the clefts of a rock formation in a clearing surrounded by cottonwood trees.

s we staggered along the trail, Rick spotted the tops of cottonwood trees in the canyon below. In a desert, cottonwoods mean water.

He took off at a near run.

I struggled to keep up.

“Hang on!” I called.

Rick paused briefly, then forged ahead.

“Cottonwoods!” he yelled.

Understanding the significance, I quickened my pace. As we began our descent into the canyon, I tripped and landed on my backside. I also wet my pants.

At least I can still pee.

I bounced and slid down the rest of the ridge. At the bottom, I rose shakily to my feet, determined to catch up.

“Water!” I heard Rick yell. He sped across a wide, dry streambed and disappeared into the cluster of cottonwood trees.

“Bring it to me!” I begged. My legs were so weak that I sank to the ground, cringing when my bruised tailbone made contact.

But Rick didn’t answer. He was following the sound of running water deeper into the cottonwoods. He spotted a brown puddle glistening in a shallow ditch. Rick dropped to his knees, dipped his container into the filthy water and drank.

Then he discovered the source of the water — a tiny, triangular spring hidden beneath a large limestone rock. Once again, he filled his container. This time, the water was clear.

“Water!” Rick yelled.

Once again, I stood up and lurched on uncooperative legs toward the sound of his voice.

I found Rick crouched over the spring. Huge cottonwoods loomed over a small clearing. I flopped down, propping my head and shoulders on a small boulder, while Rick filled my bottle with water. I guzzled it, staring up gratefully at the rustling leaves of the trees that seemed to hover protectively over us.

That water will forever remain the best thing I’ve ever tasted. A hint of earth and metal, yes. But we’d gone at least 27 hours without anything to drink. Our little spring not only quenched our thirst, it gave us new hope: We might actually make it.

Darkness descended. We would have to spend another cold night on the ground. But we were so giddy over the water that this didn’t bother us at all. We laughed and drank and cracked jokes.

“You realize we’ll probably have to take antibiotics when we get back?” I said after draining the contents of another bottle. “But it’s totally worth it.”

“And you realize that a lot of critters probably use this watering hole, right?” Rick asked.

“They might show up tonight.”

“I’ll fight them for it,” I said.

I looked down at my damp shorts. “I can’t sleep in these. I’ll freeze,” I told Rick.

And I’ll smell like pee. Will that attract animals?

I took off my shorts and dribbled a little water from my bottle on the worst spots. Then I spread them out on a rock to dry. I also took off my tank top and sports bra, both dotted with thorns and cactus needles. Rick gave me his long-sleeved shirt, which had fewer needles. Then he took off his shorts, saying he would wrap them around his arms and chest.

nce again, the temperature dropped into the low 50s. The wind blew harder that night, chilling us even more. We rearranged ourselves constantly before Rick dozed off.

In the middle of the night, I became convinced that a rock formation with a small tree growing out of it was a mountain lion watching us.

I jabbed Rick. “Do you see a mountain lion?”

The first time I woke him, Rick was alarmed.

Then he glanced at the spot I’d pointed to. “No,” he groaned. “It’s just a rock. And trees.”

The second, third and fourth times I announced the presence of a mountain lion, my husband merely lifted his head and muttered, “No. It’s not a lion. There is no lion.”

Once convinced that we weren’t being stalked by a large cat, I fixated on what awaited us in the morning:

More walking on bruised, throbbing feet.

More searching for overgrown cairns.

More panic each time we lost the trail.

Maybe we can follow the streambed or find a road. Maybe we can just stay here.

“I don’t want to get on the trail again,” I told Rick. “I can’t take take another day like today. I just can’t.”