After 27 hours without water, Cathy Frye and Rick McFarland find a spring. But it's too small to sustain them.

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette/RICK McFARLAND

Rick and Cathy followed this steep and rocky trail down into Fresno Canyon. Cathy slipped and fell several times during their descent.

IG BEND RANCH STATE PARK, Texas — Rick and I awoke before dawn, shivering from the cold and covered in goosebumps.

It was Oct. 4, a Friday. Our “day hike” had now devolved into a 48-hour excursion through hell. It seemed longer, though. The desert had stretched and twisted our sense of time and reality. We were beyond exhaustion. Our bodies couldn’t take much more.

As the pink glow of sunrise illuminated the tiny spring where we’d spent the night, Rick studied the map.

“We have to get back on the trail,” he concluded.

I knew we couldn’t stay here. The spring was too small to provide adequate water for the two of us. And after two days without food, we felt weak from hunger. No one knew we were out here, lost. No one was looking for us. We had to keep going.

But the prospect of yet another day of finding and losing cairns filled me with dread and numbing fatigue.

Before we left, we drank two full bottles of water each. Then we refilled our two aluminum containers for that day’s hike. I mentally kicked myself for losing my fanny pack the day before. It had contained all of our empty plastic bottles, which we could have filled at the spring.

Rick took a few photos. I looked longingly at the cluster of cottonwoods, then trailed despondently after him to the wide streambed that cut through the canyon.

Rick scouted for the trail but saw no cairns. Then, just like on the first day, he spotted a couple of faded ribbons tied to the branches of a mesquite tree. “This has got to be the trail,” he said, beginning his ascent.

Reluctantly, I followed.

Specail to Arkansas Democrat-Gazette / RICK MCFARLAND

Cathy Frye drinks a container of water as she and Rick McFarland prepare to leave the spring they found the night before. The couple spent the night at the base of the large rock formation.

s we climbed out of the canyon, Rick spotted a cairn. We’d found the trail.

He turned and aimed his camera at me.

“Pictures? Now?” I asked in annoyance.

“The light’s pretty,” he replied.

I offered a strained smile while he clicked away.

As we hiked, I focused on Rick’s feet, stepping exactly where he stepped to avoid the cactus and catclaw. I had lost my hiking stick; so, each time we had to climb out of an arroyo, I held on to Rick’s hiking stick while he pulled me along behind him.

And then, just like the previous two days, we lost the trail. I cried silently as Rick scouted for cairns.

The desert, it seemed, was determined to hold us captive. We would die out here. Maybe someone would eventually find our bodies. At least then our children would know what had happened to us.

“Dammit!” Rick shouted. “I know the way! My truck —” he pointed with his hiking stick — is THAT WAY! We are done with the damn markers.”

And with that, we abandoned the trail and its elusive cairns for good.

For the next five hours, I asked Rick over and over: “Do you know where we’re going?”

At first, he tried to be honest. “I think I do. My truck should be over there.”

But as I continued to question him, Rick’s patience lessened and he became more declarative: “We are going the right way. I know where we need to go.”

Rick had recognized a view we’d taken in while hiking the first day on the West Rim. He knew if we headed that way, we would eventually stumble across the trail we had set out on two days earlier.

We did reach the trail.

But neither of us recognized it.

We crossed it and kept going.

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette / Rick MCFARLAND

The spring that Rick McFarland found in a clearing surrounded by cottonwood trees.

ick kept a close eye on the time as we hiked silently up and down steep arroyos. We had until 2 p.m. to find the trailhead. Otherwise, we would have to stop and take shelter from the sun. My legs grew increasingly wobbly, and, as the morning progressed, they started giving out on me.

Each time we stopped to rest, Rick gave me only a few minutes before prodding: “Baby, we’ve got to get going. We’ve got to keep moving.”

We had only a few swallows of water left. The temperature continued its steady climb. I now had to rest every five minutes.

“We can’t keep stopping,” Rick said, looking anxiously at his watch. “It’s just going to get hotter.”

At 12:30 p.m., I spotted a small mesquite tree in a narrow ravine. Wide in diameter, it offered a larger patch of shade than the other trees we’d passed. I sat down, hard, clutching my water bottle, and trying to work up the nerve to say what had to be said.

Rick refused to sit down with me. “Baby, we’ve got to keep going.”

“I can’t,” I said. “I’m done. I’m just holding you back.”

Silence settled over us as Rick wrestled with his choices. He couldn’t imagine leaving me behind to fend for myself. At the same time, Rick truly believed he could make it back and summon help.

“OK,” he said finally, and slipped off his backpack.

I took off Rick’s shirt, which I still wore from the night before, and gave it back to him. While he dressed, I put on my tank top and lectured him about resting during the heat of the afternoon. He didn’t look well. His face was scarlet, and he breathed heavily. I feared he would suffer heatstroke in his rush to get help.

“I will wait for you,” I told him. “I can hang on. So you make sure to stop when it gets too hot.”

“OK,” Rick replied. He gave me his knife, then grabbed my water container. He had only two swallows of water left in his own bottle, but he poured half into my container.

“I love you,” he said.

“I love you too. Remember, I will wait for you.”

Briefly, we clasped hands.

“If anything happens, you tell the kids I did my damnedest to get back to them, OK?” I said, fighting back tears.

“You can tell them yourself,” Rick said.

He began to walk away, then stopped.

“Want anything when I come back?” he called over his shoulder.

“Yeah,” I yelled back. “Bring me two waters and a beer.”

Once again, Rick turned to go.

“Godspeed,” I called after him.

My husband looked over his shoulder and waved, then vanished from sight.

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette/RICK McFARLAND

Rick and Cathy cut open the pads of prickly pear cactus to suck out the juice inside. Cathy also ate the pulp, which contained hairlike needles that embedded in her mouth and lips.

had to lie on my back to scoot beneath the mesquite tree. Twigs caught in my hair, and rocks scratched my legs. I ignored the pain and curled my body around the tree’s center. Only a small spot of sunlight pierced the dense growth. I took off my hiking shoes and stuck one on a branch to block the laserlike beam.

As I arranged the shoe overhead, I laughed. Once again, I had figured out how to thwart the desert. It hadn’t beaten me yet.

I put the other shoe under my head as a pillow and dozed through the worst of the afternoon heat.

Once, I crawled out to cut and eat some more cactus, and was elated when I found a new, juicier variety. Mostly though, I worried about Rick.

Please, God, don’t let him be hurt or dead out there.

Late that afternoon, I thought I heard a plane. I managed to stand and wave but didn’t see anything. When the heat grew too intense, I squeezed myself into a small, narrow hole under the tree. It was a tight fit, but I immediately felt cooler.

My tree was rooted in a deep and rocky ravine that sliced through a narrow mountain cut. Large boulders, ringed by clusters of prickly-pear cactus, stood sentry. Off to my right, a huge rock formation loomed in the distance. I could see only a patch of sky.

My world was now very small, but it made me feel safe and protected. Hidden by the tree’s low branches, I peered out only occasionally at my surroundings.

My aluminum container still held a minuscule amount of water, maybe a swallow. I sipped at it between naps. But as the day faded into dusk, I abruptly started dry-heaving. I stopped drinking for a while. I couldn’t afford to be sick. I knew I was already severely dehydrated. I’d spent much of the afternoon pinching my arms. Each time, the skin remained folded.

Every so often, I yelled, hoping that someone might be looking for us. It took a lot of physical effort, so my calls for help were punctuated by long gasps for air. Even so, I didn’t just scream for help. Rather, I summarized what had happened to us and described in detail the rock formation that towered in front of me: “It has three chimneys the same height, and a fourth that is taller than the others!”

After the dry-heaving finally subsided, I drank the last of my water. Still, I kept the bottle close to me, even when I changed positions underneath the tree. That bottle became my talisman. Sometimes I opened it and smelled it, thinking longingly of our spring. I even cradled it while dozing.

God, I’ve tried to be a good person. Please forgive me for the times I wasn’t. And please take care of my kids. Let them know how much I love them.

Let me be able to look down on them and let them be able to feel my presence. Please take care of my parents and sisters and friends. And please, if it’s not too late, help Rick get back to the truck so that the kids will have at least one of their parents. …

I asked God to please not let death be too painful.

If it happens, let it be from hypothermia, I prayed, remembering accounts of how freezing to death is almost like falling asleep.

I also accepted that Rick might not make it either. I tried to visualize 10-year-old Amanda and 8-year-old Ethan’s new lives without their parents — where they would live and go to school. I didn’t allow myself to think about their reactions to our deaths, though. That would have broken me.

I recited the Lord’s Prayer. I tried to do the same with the 23rd Psalm, but could remember only bits of the verses I’d memorized as a child.

I spent a lot of time worrying about my parents. Did they suspect anything was wrong? By now, they should have heard from us.

Please, God, give them the strength to deal with this.

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette / Rick MCFARLAND

Each year, Frye's parents, Jim and Mary, keep the couple's two children, Amanda, now-11, and Ethan, now-9, while Rick and Cathy visit the Big Bend region of Texas.

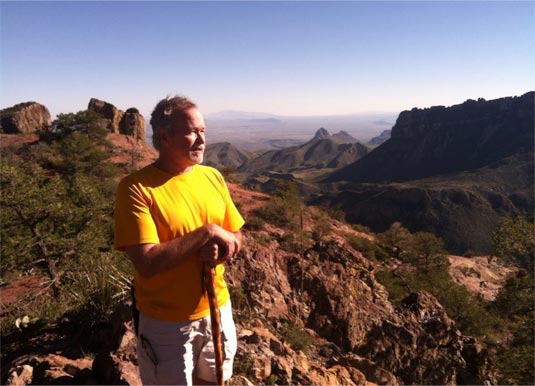

ick initially made good time on his quest to find the trailhead and our truck.

By midafternoon, however, the sun’s heat burned through his hat and and clothing. Rick swigged the last bit of water in his bottle and squeezed himself under a creosote bush. He hung his hat on a limb to block some of the sun.

At 58, Rick worried that he was pushing himself too hard in the extreme heat.

At 1:42 p.m., he tried to send a text to my dad: Help near truck.

Just as it had for the past two days, the phone offered a terse response: Not delivered.

Rick turned it off and repositioned himself to catch a breeze flowing through the canyons. He was desperate to get back to our Chevy Silverado and let someone know that I was stranded in the desert. At the same time, he just didn’t have the energy or stamina to get up and resume hiking in such extreme heat.

He also had started to doubt that he knew where he was going.

“Help!” he yelled. An echo was the only response.

ick spent several hours huddled under the creosote bush. But as the sun moved across the sky, its rays pierced Rick’s cover. Just ahead, a pile of rocks offered better shade. Rick pulled himself up and slung his camera over his shoulder. Several times, he’d thought about ditching it. The Canon was heavy and cumbersome. But as a photojournalist, Rick just couldn’t bring himself to leave his camera.

When he reached the rocks, he found a formation that resembled a chaise lounge. A looming ridge offered the best shade he’d found all day. While sitting in his stone “man chair,” Rick began to lose hope.

He thought of all the things he would miss — summer afternoons at the pool with the kids; deer hunting in the Arkansas woods; sitting on the front porch with me while our children played with the water hose and chased fireflies.

Rick yelled for help once again, but no one answered.

I cannot sit here. If I sit here, I’m going to die. If I die, Cathy’s going to die.

Fifteen minutes later, Rick stood up and rounded the corner of the ridge. Once again, he felt the sun’s stinging heat.

He saw another rock. It wasn’t very big, but the ground sloped down on one side, allowing him a bit of shade if he positioned himself just right.

I’ve got to go, Rick told himself, checking his watch. It was 6 p.m. Only a few hours until sunset.

hat evening, my thirst was so fierce that when I wet myself, I tried to suck the urine from my shorts. But there wasn’t enough liquid. Defeated, I reached up and hung the shorts from a limb just a few inches from my head.

I thought of the knife Rick had left me.

Can I?

I unsheathed the 3-inch blade, feeling no queasiness as I tested the edge on my thumb and finger.

The knife was too dull to cut my skin. So I plunged its point into my left forearm. Then, still pressing down, I dragged the tip of the blade across my skin.

Six times, I sliced into my arm, but my severely dehydrated body yielded only a few drops of blood. Still, I sighed with pleasure when the metallic flavor skimmed my taste buds.

Why didn’t I think of this earlier?

At any other time, I would have cringed at the thought of deliberately cutting myself. But after three days in this barren world, where I now lay alone and dying, it seemed rational. I had assured Rick that I would wait for him, and I would do whatever it took to keep that promise.

Still, I prayed that God would let me drink water one more time — either before I died or when I reached heaven. I just wanted to taste it again. And I continued to yell periodically for help.

I realized that only a miracle would save me at this point. Even so, I couldn’t fathom that I would miss Christmases and birthdays, weddings and grandchildren. I couldn’t accept that I would never again feel my children’s small arms around my neck, or feel their breath against my cheek.

Ethan and Amanda had been antsy about our trip this year, and I’d assured them that Daddy and I knew how to take care of ourselves.

If I died out here, I would do so as a liar.