When Cathy Frye's legs finally give out, she tells her husband: Leave me. You're our only chance.

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette/RICK McFARLAND

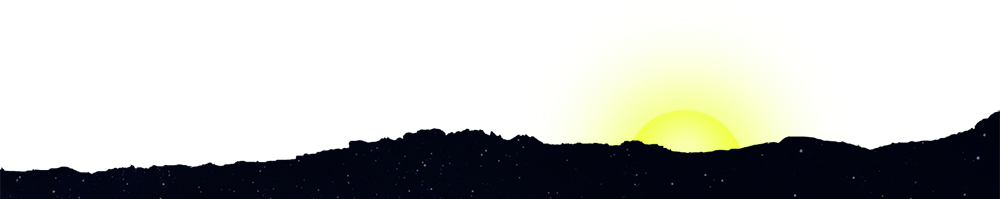

The terrain in Big Bend Ranch State Park offered little cover from the scorching sun.

IG BEND RANCH STATE PARK, Texas — Rick looked at the sea of cactus ahead of him and felt his last bit of hope ebb away.

The sun was sinking toward the horizon, and the oppressive heat had lessened a bit. Even so, Rick was near the end of his endurance.

He hadn’t eaten for 72 hours. He’d hiked all afternoon with only one swallow of water in his canteen to keep him going. And still — there was no sign of the trailhead, no indication that he was even headed in the right direction.

It was Friday, Oct. 4. We had now been lost in the Chihuahuan Desert for three days.

It would be so easy to give up, so easy to welcome death rather than to keep fighting it. He could just stay right there, propped up against a boulder, and go to sleep.

But then Rick thought of me — lying helplessly underneath a mesquite tree, counting on him to find help.

If he died, I died, too.

Drawing on his last reserves of strength, he pushed off against the boulder and stood up. A glimmer in the distance caught his eye.

Is that my truck?

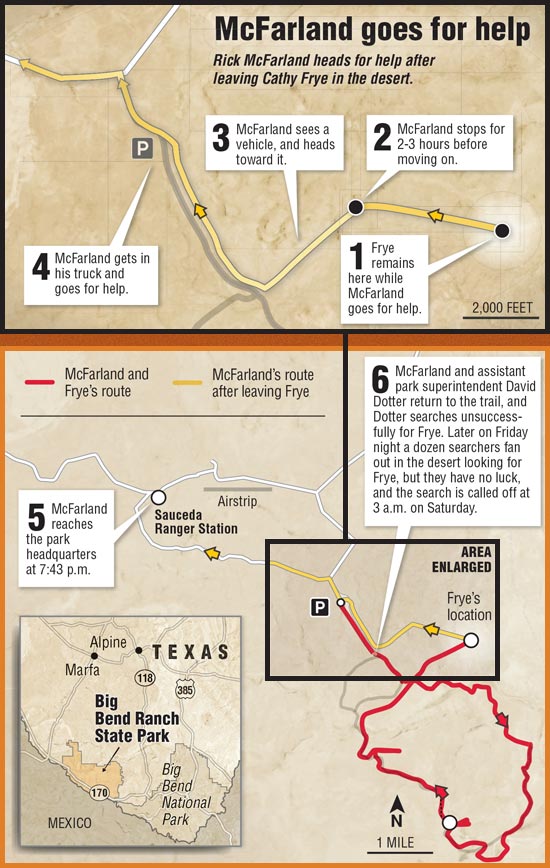

Rick grabbed his camera, took a picture, enlarged it and stared at a black SUV on the screen. It was parked at the trailhead we had been seeking for the past three days. Our truck waited just a mile down the road from that SUV.

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette/RICK McFARLAND

At 6:30 p.m. on Oct. 4, 2013, a glint in the distance caught Rick's eye. He shot a photo and enlarged it on his camera. The shiny speck was an SUV, parked at the trailhead. Rick found his truck nearby.

ar!” Rick bellowed in the direction where he’d left me earlier in the day. There was no response. He’d covered more ground than he thought, and I was far out of earshot.

“Help!” he called out, hoping the SUV owners would hear him. And then he plowed through the cactus toward the vehicle.

When he reached the SUV, Rick peered through the windows and tried the doors. No luck.

Rick took off, wondering if our Chevy Silverado would still be parked down the road. What if park rangers had towed it away? What if drug runners from nearby Mexico had stolen it?

But as he rounded a curve, he spotted the top of our truck in the distance.

When he reached the pickup, Rick opened the passenger door, unfastened the ice chest sitting on the passenger seat and grabbed a bottle of water. He turned on the ignition, guzzled the water and plugged in his phone. Hurriedly, he composed a text to my dad, hoping that his phone might finally get a signal on the way to park headquarters.

Rick downed a second bottle of water. Still thirsty, he reached for another, but found only beer. He gulped down a can of Modelo.

As he sped toward the ranger station, Rick tried calling 911 to no avail.

But at 7:28 p.m. he heard the phone’s familiar whoosh as his text to my dad went through.

Call 911 send to puerta chili trailhead

Special to the Democrat-Gazette

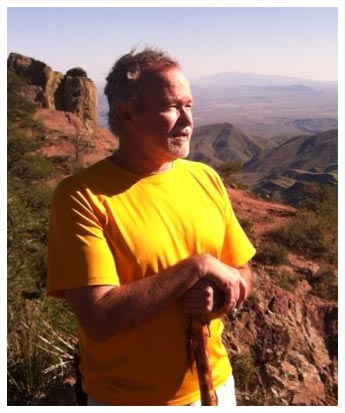

Rick McFarland on a previous hiking trip.

ifteen minutes later, Rick roared up to the park’s headquarters, blaring his horn and yelling. His erratic driving caught the disapproving eye of the assistant park superintendent, David Dotter.

I’m going to have to have a chat with this guy, Dotter thought. He wasn’t on duty, but his residence is at the headquarters.

Rick stopped the truck, and approached some park visitors. He told them we’d been lost in the desert and that I was still out there. Then he asked if he could buy some water from them. A women gave him eight bottles but refused to take any money.

“You just go find your wife,” she said.

Rick caught sight of Dotter.

“Are you a ranger?” he asked. “My wife and I have been out in the desert for several days. She’s still out there. I left her.”

“Hang on,” Dotter said. “Let me put on my uniform.”

First, however, Dotter went to the residence of another employee and asked him to start gathering rescue equipment.

On the way to the Puerta Chilicote trailhead, Dotter called the park superintendent, the Presidio County sheriff’s office and the county’s emergency medical services.

When they reached the trailhead, Rick pointed out at the desert and said, “I think she’s about a mile to a mile and a half in that direction.”

“Do you want to go with me?” Dotter asked.

“Yes,” Rick blurted. But even as he answered, he realized he couldn’t help in his condition.

“No, I can’t,” Rick told Dotter. “I’m done. I spent all of my energy making it back to the truck. I don’t want to hold you back.”

Dotter said other people would be on the way. “Tell them where I went in and where I’m going.”

Using his truck’s loudspeaker, Dotter tried to call out to me: “Cathy, this is a park ranger. I am coming to get you.”

Dotter left his patrol lights flashing. They would serve as a point of reference for him as he hiked. And maybe, he thought, the woman lost out there would see them. He grabbed his backpack and a flashlight, then vanished into the darkness.

Rick could hear Dotter calling my name. He fully expected the park ranger to find me. His primary concern was whether I would be able to walk out on my own.

When Dotter returned alone, Rick was stunned.

Did she move?

Dotter called the Texas Department of Public Safety and requested a helicopter. Meanwhile, other people started to arrive — Presidio County Sheriff Danny Dominguez and a couple of deputies, one of whom had once worked at the park; the park’s interpreter; two Presidio County game wardens; and paramedics.

Dotter asked two of the men to conduct a hasty search. Just like Dotter, the pair returned alone.

By 10:30 p.m., a dozen searchers had assembled at the trailhead. Dotter handed out flashlights and the group fanned out. Walking 30 to 40 feet apart, searchers hiked toward the area Rick had indicated, yelling my name.

Meanwhile, one of the paramedics insisted on examining Rick. After checking Rick’s blood pressure twice, the paramedic noted it was high.

“Well, it’s gonna be high,” Rick said. “I’ve been out in the desert for three days and two nights, and my wife is still out there.”

“I still think I should take you in and check you out,” the paramedic said.

“I’m not leaving until they find Cathy,” Rick replied.

Special to the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette / RICK MCFARLAND

Assistant Park Superintendent David Dotter, left, with Park Superintendent Barrett Durst

- Mouse Over To Enlarge -

s temperatures plunged, I drifted off under a spectacular star-filled night sky.

I don’t know how long I slept. Exhaustion had finally overtaken my thirst, and even the night’s chill had ceased to bother me.

At some point, the unmistakable staccato thrum of a helicopter roused me from a fitful sleep.

A searchlight blazed from the chopper. Elation swept over me. Rick had made it back to the trailhead and summoned help. People were looking for me. “Thank you, God,” I sobbed.

Then came the doubt.

Oh, God. What if Rick didn’t make it? What if they found his body? Or maybe he’s just hurt. Did my parents get worried and call the park? I was supposed to call them today.

“Rick!” I yelled, then used my childhood names for my parents: “Mommy! Daddy! Help me! Please, help me!”

The helicopter flew slowly and methodically, back and forth across the horizon.

They can’t see me if I’m under this tree.

Frantically, I scooted out from under the small mesquite that had sheltered me from that day’s blistering sun. Too weak to stand, I used my hands and feet to crab-walk up a small incline just a few feet away from the tree.

“I’m here!” I yelled. “I’m here!”

Each time the helicopter disappeared from view, my hopes plummeted.

“I am HERE! Don’t you give up on me!”

If they have a spotlight, they probably aren’t using infrared, right? Hell, I can’t stand. How can I make them see me?

I decided that if I lay spread-eagled, I might be more noticeable. But I was cold again, so I settled for tucking my arms around my chest with my legs fully extended.

In the end, it didn’t matter. The helicopter’s spotlight never illuminated the deep ravine where I lay.

he helicopter left about 2 a.m. My hallucinations began soon after.

First, I became convinced that I was one of three missing people. When one of us was spotted by the helicopter, a searcher on the ground would send up a flare. Then, a large, neon-green constellation would appear in the night sky.

When I saw three constellations, I knew that I, too, had been found. Now all I had to do was wait for someone to come and get me. The constellations were beautiful — three-dimensional and appearing to almost touch the ground. The light radiating from them pulsated. I was entranced.

Soon, the constellations disappeared. Another hallucination took hold, convincing me that I was covering a news conference. As I wallowed around in a pile of cactus and desert vegetation, I blamed my discomfort on uncomfortable seating.

The topic of said briefing: my rescue.

A group of Middle Eastern women also were at the news conference to promote a new organization. I asked them to take me out for coffee so I could interview them. Once at the coffee shop, I planned to order a lot of water instead. I hoped they wouldn’t mind that I had tricked them into taking me there.

The storyline changed again. Now I belonged to a commune whose residents lived primarily outside. I was in charge of the kids, including a teenage girl who kept wetting the bed. This, I think, was an “explanation” for what was happening as my physical condition worsened. Fluid leaked from my body as my kidneys, heart, liver and lungs suffered from the varying extremes of heat, cold, exertion and severe dehydration.

Organ by organ, my body was shutting down.

ll Friday night, Rick had remained confident that rescuers would find me quickly.

But at 3 a.m., Barrett Durst, the park superintendent, called off the search. They would start again at first light.

Rick used someone’s satellite phone to call my parents, who had been trying frantically all night to find out what was going on after receiving Rick’s Call 911 message.

When they answered, Rick finally had to say what he’d been dreading: “I left Cathy and now I can’t find her. We’re going out again when the sun comes up.”

Even after hanging up, he continued the conversation in his head: I am so sorry for losing your daughter.

Rick headed to the bunkhouse, which offered dorm-style sleeping accommodations, a large living and dining area, and a commercial kitchen where the staff prepared meals for park visitors. Before going inside, he stopped at our pickup to retrieve his duffel bag. In the truck he was greeted with the sight of my belongings: clothes strewn across the top of my bag, toiletries, books and empty sparkling-water bottles.

As he sifted through my things, he cried.

Oh, my God. She’s just all over my life, and I don’t want something to happen that destroys it.

Rick went into the bunkhouse, found an empty bed on the men’s side, then went to take a shower. He did a double-take at his reflection in the mirror. His skin was gray, coated with dirt from the desert, and his hair stood up in tufts. Cactus scratches covered his legs.

After his shower, Rick tried to sleep. But guilt weighed too heavily on him.

She’s still out there. Why can we not find her? Could she have even walked? How far could she have gone? Could she have tried to follow me? No, I don’t think she could have. She wouldn’t have wanted to climb up that hill… .

ick finally dozed off, but soon woke to the sounds of activity. He dressed and headed into the living and dining area. All chattering ceased as every person turned to look at him. Rick poured a cup of coffee but refused to eat breakfast.

Outside, the park headquarters buzzed with activity as an increasing number of searchers prepared to head out.

“You can ride with me,” said Dotter, who planned to set up a command post at the Puerta Chilicote trailhead.

As they drove, the pair passed trailers from which several horses were being unloaded. Two of the animals were trained to carry out dead bodies.

As soon as Dotter parked, Rick jumped out and headed toward the trailhead, where two dozen people readied for the search.

“Wait,” Dotter called to Rick. “We’ve got to figure out where we’re going.”

“I’ve got to find where she is,” Rick said. “I’m going.”

Ignoring the calls to stop, he strode back into the cactus.

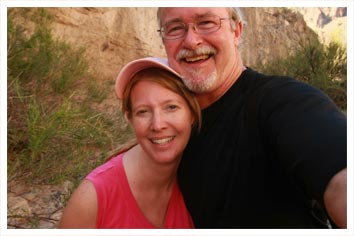

Special to the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette / RICK MCFARLAND

Rick and Cathy pause to take a photo during a previous hike at Big Bend National Park in 2010.